Maps of neighborhood opportunity across the United States show clear and painful patterns of racial and ethnic inequities. White and Asian children tend to live in resource-rich neighborhoods with quality schools, parks, housing, clean air and economic opportunities; Black and Hispanic children tend to live in neighborhoods with fewer resources that support their healthy development.

These patterns did not happen overnight, and they did not happen accidentally. They are a product of racist policies that intentionally directed or denied investments and resources across neighborhoods based, in part, on the race and ethnicity of their residents. Policymakers and others in power used these strategies deliberately to protect the social and financial interests of some families—usually White and U.S.-born families—at the expense of others—usually Black, ethnic minority and immigrant families.

As scholars of racial and ethnic equity and child opportunity, we seek to understand the link between the gaps in opportunity our children face today and the inequitable and discriminatory policies—present and past—that have created or reinforced these gaps. We seek to document and monitor these entrenched patterns of segregation and inequity that hurt our children; understand how they came to be so woven into the fabric of communities; and determine how they can be undone or mitigated to create more equitable futures for all children. It is essential that we name, describe, map and understand the effects of present and past policies that have bestowed access to resources to certain communities while denying it to others.

From Redlining to Child Opportunity

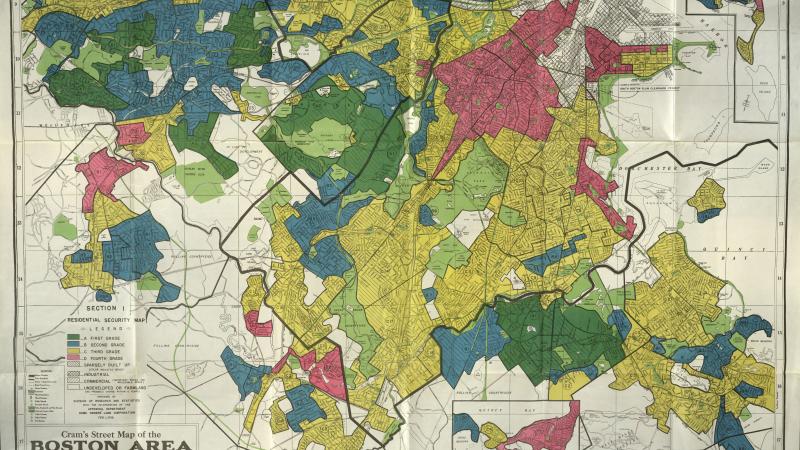

With From Redlining to Child Opportunity: Confronting systemic racist residential segregation, we have created the only dataset available that maps child opportunity today to “redlining,” the neighborhood risk grades assigned to communities by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) between 1935 and 1940. Tasked with providing mortgage refinancing to struggling homeowners during the Great Depression, HOLC assigned neighborhoods with grades that evaluated their “mortgage security” based, in part, on the racial and ethnic makeup of who lived there. The red color used on HOLC maps to delineate the most risky or “hazardous” graded neighborhoods gave rise to the term “redlining.”

HOLC grades were not an isolated policy. They were part of a system of discriminatory practices that excluded Black and other families from living in certain communities and influenced which neighborhoods would receive investments.

There is evidence that the effects of these redlining practices, both those designed by HOLC and similar ones—for example, those implemented by the Federal Housing Administration—have continued for nearly a century (Aaronson, Hartley, & Mazumder, 2021; Aaronson, Hartley, Mazumder, & Stinson, 2023; Appel & Nickerson, 2016). By linking the HOLC grades to our Child Opportunity Index, we can see the association between past racist policies and current patterns of neighborhood opportunity for children.

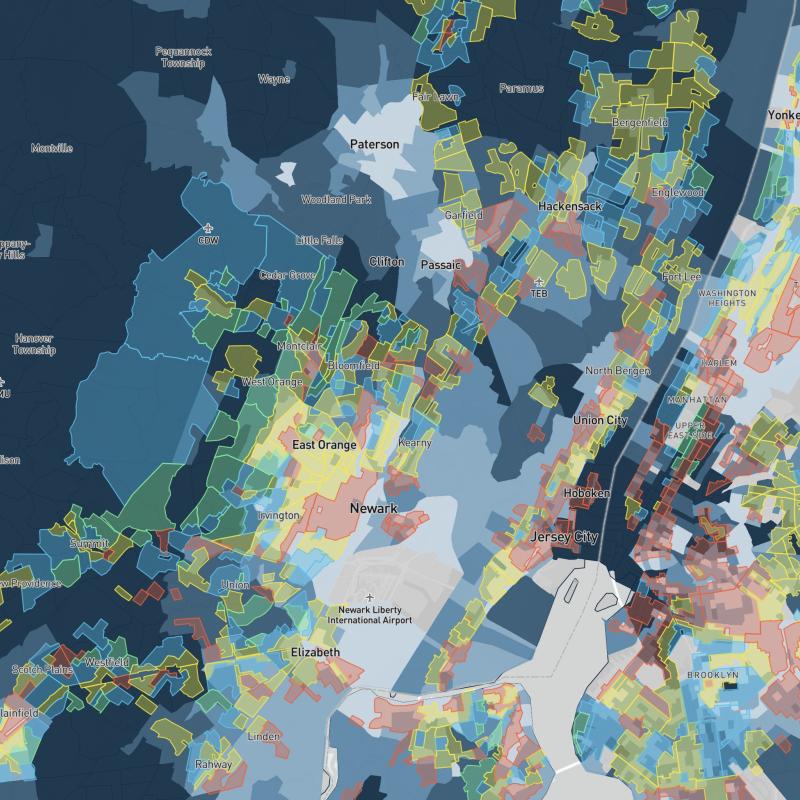

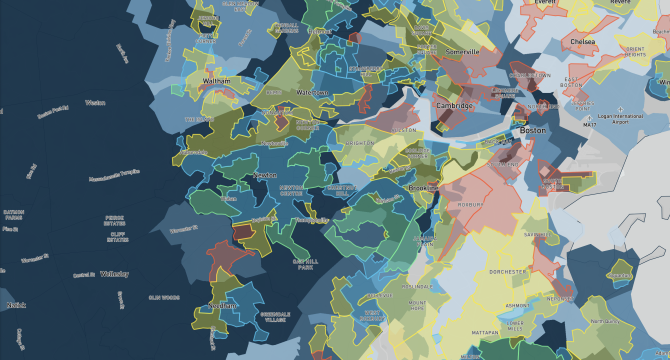

Our updated interactive mapping platform allows users to explore how these past policies relate to contemporary child opportunity. Our accompanying data stories (below) highlight what we’re learning about the effects of redlining on segregation and child health and wellbeing.

Although the effect of discriminatory policies like redlining was not deterministic, their intent was racist and thus unacceptable, and they have had a large influence on the present conditions and trajectories of communities. While many communities today thrive despite having been systematically denied resources in the past, others are still grappling with the weight of that legacy. There is much more to understand about why neighborhood opportunity looks the way it does today, but it is undeniable that there is a strong correlation between racist and discriminatory policy choices of the past and inequities in opportunity today.

We must all be mindful of the importance of using data and mapping projects like this one to support communities that have been wronged and to enhance equity for all. Our team will continue to analyze the relationship between redlining and contemporary neighborhood opportunity and child outcomes. Redlining is not just a problem of the past, and it is not the only policy that has contributed to segregation and opportunity hoarding. To that end, we hope this project will also foster improved understanding of the impact of place-based, racist policies on child and family wellbeing—and spur new applications that seek to undo these inequities.

Interactive map

On our mapping platform, zoom in on a metro area to explore how 1930s HOLC neighborhood grades overlap with contemporary child opportunity today—and see how patterns have and have not changed in the past century.

Explore now